How Generative Art is Changing: From Short-Form to Long-Form

Precision and serendipity in long-form generative art

This post has been created to add comments and a few interesting facts to the evolution of generative art as discussed by Tyler Hobbs in an inspiring essay. An outstanding artist, known primarily for his Fidenza collection, Hobbs shares fascinating insights that provide us with food for thought.

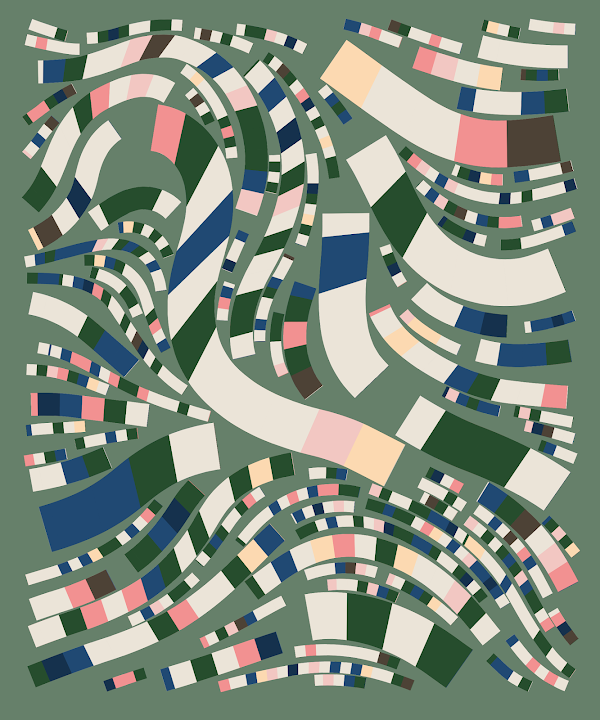

Tyler Hobbs, Fidenza 32, Fidenza 12, Fidenza 838, Fidenza 920 (long-form generative art)

He explains the differences between short-form generative art – as it has been known since the 1960s – and long-form generative art, a new and different practice that emerged recently.

While the short-form admits errors, deletions and selections, the long-form is inherently unpredictable, eliminating any form of final control.

Previously, the steps for creating generative artworks involved a curation process. The artist could create a large number of outputs and would only later narrow them down to a select set of the best highlights that were eventually presented to the public. This final selection was usually quite limited, since the artist only chose to display publicly what he/she considered good or great. This process allowed mistakes to be made without worrying too much. The artist always had the final decision about what to showcase. And so did the collector: selecting the favourite from the different options.

Instead, what we’re witnessing now is an approach where complete control over all the outputs is no longer part of the game. This is not the case for the short-form generative art that we’ve known so far, which still legitimately exists.

This new way of generating artworks is made possible by on-chain generative art platforms such as Art Blocks, Gen.Art and fxhash. As clearly explained by Tyler Hobbs:

‘The artist creates a generative script (e.g. Fidenza) that is written to the Ethereum blockchain, making it permanent, immutable, and verifiable. Next, the artist specifies how many iterations will be available to be minted by the script. A typical choice is in the 500 to 1000 range. When a collector mints an iteration (i.e. they make a purchase), the script is run to generate a new output, and that output is wrapped in an NFT and transferred directly to the collector.’

The fascinating thing is that none of the players – artist, platform or collector – can predict the game’s results, since the output will be different every time the algorithm is run, making for a great deal of curiosity.

There is also a new interaction between the artwork and the collectors. Collectors are no longer just purchasing an existing piece: they are fundamental to its generation during the minting process. Admittedly this only entails clicking a button and depositing funds, but minting is usually accompanied by an emotional involvement. The combination of unpredictability and latent expectation fuel growing excitement and wonder.

This new approach to generating artworks requires a much higher level of expertise. While randomness remains paramount, the artist has to achieve a new level of precision to reduce the risk of generating poor-quality works. The artist no longer has the chance to discard them before their public display.

In long-form generative art, the individual work is an integral part of the collection as a whole. While maintaining their own characteristics and letting serendipity play a role, all the pieces should also convey a sense of unity across the collection.

Consistent quality, high levels of diversity and coherence are therefore key factors for success.

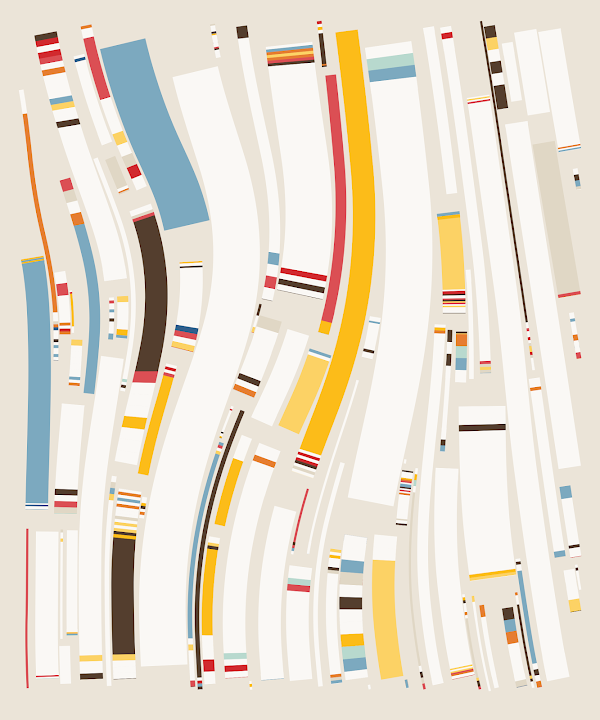

Matt DesLauriers, Subscapes #634, Subscapes #593, Subscapes #561, Subscapes #626 (long-form generative art)

Click here to read the full essay by Tyler Hobbs.